There is little available in the way of documentation of the archaeological dig at Chobham. However, a local archivist at the Chobham Museum (who asked to remain anonymous) found some sketches and handwritten notes pertaining to the discovery. These were part of a large collection of papers left to the museum by the estate of a local resident. It is not clear if they were the work of the deceased local or if that person had obtained them from their author.

What is clear from the sketches and notes, is that a significant excavation must have been undertaken immediately following the discovery, as close examination of the site is evidenced.

Notes on the reverse of the sketches give a position of: 51° 20′ 52.764” N, 0° 36′ 15.804” W, which is now the site of a small supermarket.

The Pit

‘Celtic Cross’

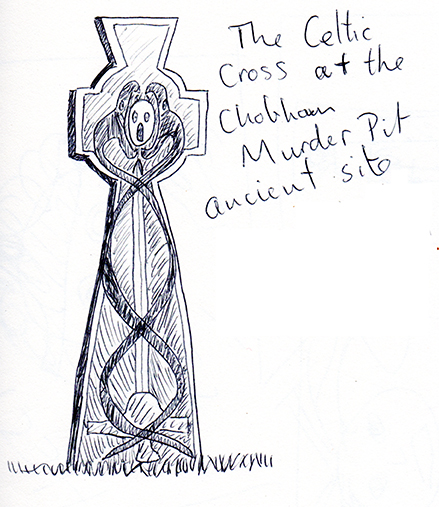

An interesting addition to the pit is the evidence of a Celtic Cross, which must have been a much later monument, possibly placed to avert evil, even before the church was built. The cross was discovered on its own, several inches above the opening of the main pit aperture, itself about three feet below the current ground level. It seems that only fragments of the cross were found and the full design extrapolated from them. The only sketch is of what the full cross might have looked like, based on other examples known to have existed in early medieval Britain.

Whilst described as a Celtic Cross, it is likely the cross was much earlier than other christian crosses.

However, given the establishment of the church at Chobham was as long as 200 years before the very first examples of Christian, Celtic Crosses were built in Ireland and Scotland, it is likely that this cross was even older and possibly one of the very earliest examples of christian art in Great Britain; if it even is christian. It has been suggested that it does not represent any known religious iconography at all, but is entirely pagan. Certainly, the imagery of intertwined serpents, sword and skull are not what one might traditionally associate with Christianity, though serpents, of course, carry a clear Judeo-Christian significance.

One theory is that the cross was a representation of Jormungandr, eating the souls of the cursed. This association with Norse mythology might date back to the earliest Viking settlements, or even to earlier ancient Britons, prior to the Saxon and later viking migrations. It is possible that it could date even earlier, to Roman times, representing elements of the Cult of Mithras, honoured by the legions. Whatever the provenance of the cross and its design, consensus is that it was placed as a protection against the malignancy of what lay below.

The archaeological notes suggest that the cross was displaced, broken and buried possibly as the result of flooding from the nearby Mill Bourne. The depth of the remains indicate well over 1,000 years of burial. This itself points to a possible explanation of the Church’s concerns, as the area was and remains prone to inundation – a natural disaster that could be seen to have divine or infernal provenance.

When the Church authorities first arrived in the seventh century, they would have seen the apparently pagan statue and possibly toppled it on purpose, leaving it to succumb to the environment. Indeed, in his famed ‘Chronicles of Surreye’ Thomas of Cebbeham (Chobham) notes that despite ‘fieldes so plentifulle, the favor of Our Lord muste be evidente’, there was also ‘a darkenesse of profanitee that shoude for eternity be covered over and never be of matter for the goode folkes of the parish’. This passage of the text, held in the vault of Guildford Cathedral, along with the renowned and mysterious Chobham Chalice, has never been released even for study, on the highest Church authority. It has been surpressed since the Convocation of 1604, at which Bishop Bancroft presented his notorious Canon 72, which sought to marginalise and heavily regulate exorcism as part of Anglican lore. The above quotation was published in an academic text on obscure agricultural matters, having been found in the personal writings of Nicholas Heath, who had been Archbishop of York, prior to becoming Lord Chancellor and proclaiming Elizabeth queen, on the death of Mary. He lived his final years and died in Chobham in 1578. Only someone of his position could have had unrestricted access to such a dangerous text as the unredacted Chronicles. His personal papers (held at the Bodleian library) show a wide-ranging interest in all matters, including both agriculture and diabolical influence in England. It is suggested that he chose Chobham as his retirement home specifically so that he could guard against the evil that was hidden there.

Some local legend suggests that removing the ‘protection’ of the cross, in fact brought about the flooding that persists to this very day.